After 4 days of kayaking and camping in Harriman Fjord (see Alaska(1)) the boats arrived to take us back to Whittier.

Our van had arrived on the last train. We loaded our gear onto the top of the van and Mike, our guide, drove it onto the Alaska Ferry that was to take us to our next destination, Valdez.

Alaska Ferry in Whittier. Notice abandoned barracks in background

Valdez, a former gold rush town, is located on the eastern side of Prince William Sound and at the end of the Alaska pipeline. It is a commercial fishing port as well as a terminal for Alaska crude and other freight.

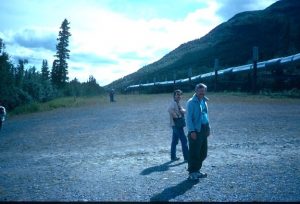

Friction from fast moving oil makes the pipe hot. The cooling fins are to keep the legs from melting the permafrost. The pipeline is elevated so that it doesn’t interfere with the migrating animals.

This was 1988, but the damage from the 1964 magnitude 9.2 earthquake was still visible in Valdez. There were several abandoned areas that looked as though the land had dropped 20 feet or more.

Thompson Pass near Valdez – the snowiest place in Alaska. One year the snowfall here was over 900 inches. The inverted “L’s” on the roadside are markers so the snowplows can find the road after a heavy snowfall.

We didn’t do much sightseeing in Valdez. We did buy a shower which set us back $3.00 apiece, and picked up some groceries. We set up our tents at a campsite on the outskirts of town. The next morning we hit the Denali Highway and headed north.

The Denali Highway was mostly gravel. It was, however, relatively smooth and wide, but traveling on this gravel at 70mph was pretty hard on tires and we had two flats along the way. Fortunately Mike had two spares. Later we found a tire repair shop that fixed the damaged tires.

After two days of driving and sightseeing we arrived at Denali National Park. This is quite a distance north of Whittier and we were no longer in an oceanic climate. Unlike the southern areas that we visited, the sky is actually blue here and the humidity is quite low. It never got dark during our stay and often became quite warm. The region is tundra and permafrost, nearly no trees. Low bushes and flowers abound.

Lynx Creek campground is located at the entrance of Denali Park and we set up camp there. From here we spent the next two days exploring the Park.

There is one road through the park and shuttle buses take visitors to the interior. We hopped on and off the buses and hiked at various places, being advised not to venture too far away from the road. We spent some time hiking around Wonder Lake, then picked up a bus to return to our campsite. The ride back took 5 hours. Part of the drive was through taiga (Russian for land of little sticks). This was tundra that could support only stunted conifers – none over 20 feet tall.

Taiga

Much wildlife was visible, including Dall sheep, caribou, grizzly, golden eagles, and small prairie dog- like mammals. Flowers of various shades abound on the tundra. Mt. Denali (named Mt. McKinley by Americans) was visible in the distance – crisp and clear. It was easily distinguished from the other mountains in that it was brilliant white while the others were green or grey. Mt. Denali is so large it creates it’s own climate and is often obscured by clouds. Because of this it is only visible about 30% of the time. We were quite lucky that the weather gods smiled down and allowed us to see this marvelous spectacle.

Denali (Mt. McKinley)

Just outside the park was a bar called the Lynx Creek Cafe. We stopped there one evening for a drink. The outdoor patio was full of adventurers of all ages – old ugly guys with beards, families, college girls with backpacks wearing shorts and hiking boots. Everyone was energized and excited. It was 2:00 AM and broad daylight, but nobody seemed to want to retire.

Lynx Creek Cafe

Chris was talking with two girls sitting at a picnic table, Mark and I were sitting at the bar. Chris invited us over to meet the girls. I said, “Ok, but don’t introduce me as your father, tell them I’m your brother”. He did, but during the conversation that followed, out of habit he repeatedly referred to me as “Dad”, so my cover was blown. The girls didn’t seem to mind and when they heard we had just bought a big jug of gin in Valdez they invited us to their tent to party further. Chris and I took them up on their invitation and Mark hit the sack.

When we arrived at their tent I broke out the gin and everyone had a drink. When the girls noticed that I put the cap back on the gin they objected, telling me I should throw away the cap because we would no longer need it. That convinced me that this crowd was too rough for us country boys and we immediately abandoned the scene. After all, that gin had to last through the remainder of our trip. These girls weren’t interested in our good looks and charming conversation, they just wanted our booze!

Hiking in Denali Park (Mt. Denali in background)

Moose in Denali Park

Sable Pass in Denali Park. Notice the nails along the bottom of the sign to prevent the grizzlies from gnawing.

Here is one reason the sign was necessary!

We spent 2 days camping by Denali Park, riding the shuttle bus, hiking, observing wildlife and generally enjoying the area. On the last night we attended a salmon bake, did some laundry, and packed our waterproof bags for the raft trip.

The following morning we drove to Talkeetna Airport where we met the guides from “Nova River Runners”, the outfit that was to take us on our rafting trip. They issued each of us rain suits and rubber boots. We had two bush planes available – one a Cessna, the other a silver-colored Piper Cub of 1940’s vintage. The Cessna was equipped with skis as well as wheels.

The Piper Cub was loaded with rafts, frames, oars, duffel, etc, and was flown by an elderly pilot that had a small white poodle as his copilot. He had been flying out of this airport since 1948 and was definitely much older than the average bush pilot.

It took several trips of about 1 hour each to get us and our gear to the top of Mt. Talkeetna, where we were to start our rafting experience.

On the plane ride to the top we flew over breathtaking scenery – mountains, taiga, muskeg, moose, caribou, and braided rivers the color of milk from rock ground up by the glaciers.

The Cessna pilot who flew the passengers must have been all of 17. On landing it looked to me as if he was going to put the plane down in the water, but he managed to land on a narrow sandbar in the middle of the river. Except for a narrow path down the center, this sandbar was covered by 10 to 20 foot high trees and brush. I didn’t realize how narrow the path was until I watched the plane taking off after leaving us on the sandbar. The wings of the plane brushed the branches on both sides. I suddenly realized why Alaskan bush pilots seldom get to be old men – our Piper Cub pilot was a rare exception.

We had almost as many guides as we had customers – Chuck and Ron from Nova Rafting, Mark, a soils expert for the state, Michelle, a biologist, and Jim, a husky native Inuit. We were treated like royalty. The guides cooked excellent meals, set up and cleaned the camps, assembled and steered the 3 rafts, etc. All we had to do was pitch our own tents, see to our personal gear, and help steer the rafts.

It took us 4 days of rafting down the Talkeetna river to get to the bottom of the mountain. We started in a valley filled with glacial outwash. The river here was swift with many channels that criss-crossed in a braided pattern. We floated for several hours and set up camp on the river’s edge.

There were many large bear tracks here. Just in case we had bear trouble, one guide carried a 12 gauge shotgun loaded with buckshot and slugs, another had a .44 magnum revolver. Normally these grizzly bears will avoid humans if possible. The trouble usually occurs when you come upon one in the bush and startle it. When walking through the brush we would sing and holler things like “Here bear “ and make lots of noise. Some campers tie sleigh bells to their shoes to announce their presence to the bears. The standing joke in Alaska is that when a bear dies and the contents of his stomach are examined, large numbers of sleigh bells are often found!

The river was a mixture of flat peaceful water and terrifying rapids, 20 miles of which went through a canyon with steep cliffs on both sides, preventing us from going anywhere but straight ahead. On one particular difficult rapid we tied our rafts and scouted the rapids from the top of a cliff – about 60 feet above the water.This part of the rapids is known as the “Toilet Bowl” and the river is squeezed between two cliffs, and makes a right turn into a flat place with an eddy. From there it makes a sharp left and shoots through a rocky place called the “Sluice Box”.

The guides decided how they were going to negotiate these rapids and we piled back into the rafts. Our guide had Big Jim the Inuit and me sit on the right side of the raft. He told us to back-paddle as hard as we could on his command. When the command came I tried to back-paddle but the water was so swift I could not move my paddle. It felt as if I had stuck it into concrete. Big Jim tried to back-paddle and bent his aluminum paddle into a 90 degree angle.

We ended up in the middle of the gorge with water roaring past us on one side. More paddling put us back into the current again and we entered the Sluice Box.

Everyone safely through, we set out down the remaining 14 miles of white water in the canyon. We camped by a gold prospector’s shack. The prospector was gone and we made use of his outhouse.

The milky color of the water is due to rock ground up by the glaciers

Michelle was taking a swim in the river and I decided to join her. I got in as far as my ankles and the pain from the cold glacial water was so intense that I popped right back out. I have previously swum in cold water in the Boundary Waters, Quetico, and even Antartica, but I have never experienced anything as painful as this. Those “Alaska wimmin” are really tough!

Chuck, one of our guides, had bought a Casio waterproof watch just before the trip. The first day into the trip the watch stopped running.

Now what do you think a normal person would do if they had bought a watch and it quit running after the first day? Take it back to the store and ask for a replacement or refund, right? Not these guys. They propped the watch up on a rock, threw stones at it, and took bets on who could break it first. They entertained themselves for over an hour playing this game. I marveled at the relaxed attitude these guys had and how it differed from that of most people I knew in the lower 48.

The next morning we negotiated the final 5 hours of river, dismantled and deflated the rafts, boarded the van and returned to Anchorage (a 3 hour drive) and the Inlet Inn, where we had previously roomed.

At this time of year Anchorage never gets dark although the sun does set. At dusk the sun sets in the west, then for the next few hours the sunset slowly moves along the horizon from west to north to east where it is now a sunrise!

It was our final day with Mike, the guide from Camp Alaska Tours, and he offered to treat us to a beer at “The Great Alaska Bush Company”. This wild frontier-type bar had topless and bottomless dancers. Nancy declined the invitation but the rest of us accepted. After all, who in his right mind would pass up free beer?

When we arrived, there was a girl dancing on the back bar. She was definitely making some fancy moves. I wanted to give her a tip, but she didn’t have any pockets in which to stash the money!

We walked around the city that evening and had dinner at a bar frequented by native Inuit people.

There were two lovers sitting in a booth. Mark wondered if they were going to kiss or rub noses!

We also stopped at the Bush Pilot’s Museum. The bush pilot’s hall of fame had no members over 33 years old. We noticed that even though Anchorage was the largest city in Alaska, it had no buildings over two stories high.

The following morning Mark, Chris and I rented a car and drove 250 miles to Homer, where we planned to do some halibut fishing. We set up our tents in a campground on a hill overlooking the town. The scenery was stunning. Homer is both a fishing and farming village and is unique for its “spit” – a narrow 5 mile stretch of land that juts out into Kachemak Bay. The water in the bay had a purple cast with a large mountain rising straight out of the water on the far side. On the spit were marinas, fish canneries, and campsites for the cannery workers.

The “Spit” in Homer Alaska

We had booked a day long trip on the “Debbie Joann”, a charter fishing boat out of Portland, Oregon. We sailed about 15 miles out to sea with 8 fishermen and 4 crew. The farther we went the rougher the sea became. The captain said that it may be too rough for us to fish and offered to turn back. We finally decided to stay out for a half day at half price.

The rollers were 8 – 10 feet high and the boat was rocking at a pretty good pace. I started fishing and my rod tip would sometimes touch the water. I was feeling fine and not a bit ill, when without any warning I suddenly lost my breakfast. I was still not feeling sick and didn’t know why that happened. Five or so minutes later I knew exactly why it happened. I became so sick that I would have had to get better before I could die!

That was quite a shock to me. I had crossed the Pacific twice on troop ships in water much rougher than this and didn’t get sick. It may have been the frequency of the waves which was much quicker, or it could have been my age or physical condition – who knows. Anyhow, I could no longer fish. Mark was in a similar condition as were over half the people on board. Chris didn’t get sick and pulled in halibut one after another.

One half hour after getting off the boat I was feeling fine. The captain filleted our fish – we had about 20 pounds of fillets. We kept two for supper and took the rest to a cannery to be vacuum packed and frozen so we could take them home.

Halibut

For our final adventure we drove to Morgan’s Landing on the Kenai River to do some salmon fishing. Many people think that if you go to Alaska to fish you will have the place to yourself with no crowding. That may be true if you fly into some remote spot with no road access, but along the Kenai when the salmon are running the fishermen are elbow-to-elbow, and the banks are so crowded you have to fight to get to the river. If you lose your place you may never get it back.

The Kenai was quite swift and milky from the glacial till. The salmon were so thick it looked as if we could walk across the river on their backs. I don’t understand how they could see our bait in that milky water and I believe many were snagged by the hook as they swam by.

We didn’t have any luck that day except that Chris caught one large salmon. Trouble is – it had already been filleted – and it was still wiggling! I know the reader will not believe this and I can’t find a picture to prove it. I can hardly believe it myself but I have two credible witnesses who swear that this event occurred.

When we flew out of Anchorage on August 1st it was already getting dark at night – a sign that Alaska was getting ready for a long dark winter and it was time for us to leave.

More photos HERE