Tom Gregory recently emailed some photos to me that he took in the ’60s while he was a student at Ravenna High School. These pictures brought back memories of the following events:

When Spohn’s TV Repair Shop in Ravenna closed and went out of business, the owner contacted me and asked if I would like to have the remaining stock of old TV’s and various electronic parts for use at the school. He informed me that there was about a truckload of stuff and I had to take it all. When he said a truckload he wasn’t kidding. The stuff completely filled my flat bed truck. There was everything from TVs in various stages of dis-repair to vacuum tubes, capacitors, resistors, knobs, wires, nuts, bolts and screws, along with things I didn’t recognize. This was an experimenter’s dream!

This stuff filled one corner of the physics lab. One problem that immediately needed to be addressed was that some of the TVs didn’t have a cabinet and the picture tubes were exposed. This needed to be taken care of for two reasons:

1) A picture tube acts like a large capacitor and can hold a lethal charge of electricity for a very long time.

2) If broken, the tube’s high vacuum will make it implode and go off like a bomb, causing glass shards to be violently thrown around the area – not a good thing to have in a school full of ornery kids..

So the first thing I did was remove the picture tubes from the TVs that were not to be repaired.

We repaired the remaining TVs, then sold them and used the money to buy lab equipment. Others were torn apart and the parts used for various projects. The power transformers and rectifiers were used to power radio gear and for power supplies in the lab. We also built some 6 volt power supplies as battery replacements for Mike Lenzo’s 6th grade science classes.

Now I had to decide what to do with those potentially dangerous picture tubes. I couldn’t just throw them away because they had so many interesting possibilities.

Tom Gregory was one of the students who first got me interested in ham radio. He was also the school photographer and an electronics experimenter. One day Tom showed me his recent project – a device that would allow sound to fire a strobe light. With it he could take a photo simply by clapping his hands.

When I saw this device my evil mind went into high gear. Why couldn’t we use this to take a high-speed action shot of a TV picture tube imploding? The sound of the implosion should set off the strobe light and cause the picture to be taken.

There were several problems to overcome. How and where could we safely do this, and how could we do it without sending the instigators (us) to the hospital? We consulted with “Otch” Houston, the chemistry teacher, who was also interested in this project.

Otch had recently built a new house with a large and almost empty basement. We decided that this would be the perfect place to conduct our experiment. I didn’t think his lovely wife, Dianne, would let some weirdos blow up stuff in her new house, but we convinced her that this was in the interest of science and the future of mankind, and we would clean up any mess we made and fix anything we broke, so to my surprise she foolishly consented.

We hung a pulley on the basement ceiling with a rope running through it. On one end of the rope we tied a large brick, the other end we strung behind a barrier where we could all hide and be shielded from the flying shrapnel. We then put a picture tube below the pulley where the brick would fall. Tom set his camera on a tripod, turned on the strobe device, turned off the lights and opened the camera’s stutter. We then crouched behind the barrier, hoisted the brick up to the ceiling, and let ‘er fall.

The resulting implosion was much more violent than we had expected- sounding as if a shotgun had been fired. It threw pieces of glass all over the basement, some as far as 40 feet. The size of the razor-sharp shards ranged from palm-size down to grains of sand.

We were so shocked at the violence of the implosion that we started talking and laughing excitedly – each of these sounds was repeatedly setting off the strobe. This cut down on the picture quality since the shutter was still open. More problems occurred when we walked over to close the shutter – each step crunched the broken glass, again triggering the strobe. To solve these problems we re-adjusted the sensitivity of the trigger device and restrained our laughter until after the shutter was closed.

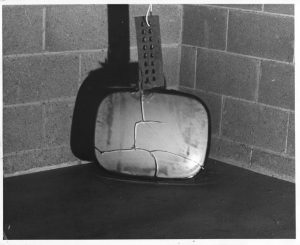

The results of our efforts are displayed below. I hung these pictures on the bulletin board at school to show the students what a dangerous device they had in their living rooms, and to convince them that a television set needed to be treated with care.

This one had previously lost its vacuum and merely broke apart

These imploded violently

Clean-up time

Tom, Otch, Gene – The Instigators

(Also read Tom’s comments below)

Gene,

For this project I built a device that would trip a relay in response to a sound. I found the schematic in the January 1965 issue of Popular Electronics magazine. It had a microphone input, amplifying stage, and sound sensitivity adjustment. Three tubes I think. Built completely from scratch from the schematic. I wish I still had it. I think it was your idea to use it to break things. The sound of the explosion tripped the electronic flash or strobe. We used Otch’s basement on Summit St. The basement was dark so the strobe illuminated the room, flash duration of perhaps a ten-thousandth of a second. The shutter on the camera was open during the flash then I closed the shutter before we turned on the room lights. We hid behind an upturned table in the dark. The brick was on a rope and pulley rig. After each tube we swept up and did another one, probably 5 or 6 of them Great fun on a Saturday night.

Tom G

From Merici/Fred:

Who said teaching can’t be fun?

Gene replied:

And they also paid me – hard to believe!